Weekly Report: March 12, 2023

Observations

The Collapse of Silicon Valley Bank

Silicon Valley Bank is, relatively speaking, just down the road from me. As one the top 20 largest banks in the U.S., it is the banker to half of the startup industry but, fortuitously, not to my employer.

At the start of this week, SVB held about $170 billion of deposits from its customers. On Thursday, it fell victim to a bank run. SVB’s customers, within the space of about 24 hours, withdrew $40 billion—a quarter of its deposit book. This is a tremendous amount, and SVB did not have enough cash on hand. In fact, at the end of the day, it had a cash shortfall of almost $1 billion dollars. When a company is unable to pay its debts as and when they fall due (and on Thursday, $40 billion suddenly fell due), the company is considered insolvent and cannot continue business as usual.

On Friday, SVB was placed into receivership. A federal government agency called the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), took over management of SVB and immediately closed it for business. Anyone still with money in SVB was now unable to get it out. “Anyone” turns out to be mostly startups, who are now facing an uncertain and very stressful few days.

But how did we end up here? Why did customers suddenly want to pull out $40 billion? And if took in $160 billion in deposits, why did they have not enough cash to pay $40 billion back?

What happened?

We don’t normally think about things in this way, but a deposit in a regular bank account is basically a loan to the bank that you can ask the bank to repay at any time (which essentially happens when you go to an ATM and withdraw cash, or ask Venmo to send money from your bank account to a friend). In exchange for lending money to the bank, they pay you interest (normally). Banks use your money to make money. Typically, this is done by lending those deposits to other people, at higher interest rates. So, for example, you might lend the bank $100,000 and they pay you 1% interest, but then someone else might borrow that $100,000 from the bank to buy a house (i.e. a mortgage loan) and pay the bank 3% interest. They pocket the 2% difference.

But the loans that banks make aren’t “on demand”. If you have a 30 year mortgage, you only need to repay a certain amount, plus interest, each month. The bank normally can’t force you to pay more than that. On the other hand, the money you lend to the bank in a regular savings account is “on demand”. This is sometimes referred to as “borrow short and lend long” and is just how banks work.

So, given that timing mismatch, how can the bank lend any money out? After all, it’s no good if you go to the bank one day and want your $100,000 back, only to be told “sorry, we lent your money to someone else and we have to wait 30 years before we get it all back”.

Enter “fractional reserve banking”. In reality, people rarely ask for all their money back at once, and never does everyone ask for all their money back at once, so banks only need to hold back a fraction of their deposits as cash, and can lend the rest of it out (or invest it in other things that are expected to produce a positive return). The fraction that banks need to hold in reserve is fittingly called the reserve requirement, and is set by banking regulations.

There are situations in which unusually high amounts of withdrawals may exhaust a bank’s reserves, but there are usually also facilities available under which banks can borrow money (typically from other banks) on a short-term basis to fill any holes while they scramble to convert their other assets (loans and investments) back to cash.

SVB was in a slightly different situation, but the basic principles are the same. The main difference is that their client base is heavily composed of tech startups. Most tech startups are not profitable or cash flow positive, so they finance their operations by raising equity financing (giving up a piece of the company in exchange for money), rather than debt financing (paying interest in exchange for money). Missing an interest payment on a loan can be deleterious, so when you’re not reliably making money as a startup, debt can be dangerous and is usually avoided. As a result, SVB didn’t have a lot of avenues for lending out the money it had received from its customers to other customers, so it needed to find another place to invest that money to earn a return.

For this, SVB invested a lot in debt in the form of U.S. treasury bonds and mortgage backed securities. When you buy a U.S. treasury bond, you are lending the U.S. government money, and they pay you interest. Treasuries are considered “risk free” in the sense that the U.S. government will always be able to pay you back. They can do this because they can just print money, if they need to. (Let’s leave to one side for now the game of chicken that politicians play every few years with the debt limit.) So from a creditworthiness perspective, treasuries are a very conservative investment vehicle. They are also a very liquid asset, which means there is a deep and active market that lets you buy and sell a lot of bonds quickly.

Because the short-term interest rates have been near zero for so long, SVB decided to invest in $90 billion worth of longer-term bonds that returned a little less than 2% of interest per year, and the full amount of principal after several years.

During the pandemic years, investment in tech startups blossomed, with equity financing pouring into companies at ever increasing valuations. Consequently, because of how concentrated SVB’s client base is in tech startups, their deposits trebled from about $60B at the start of 2020 to almost $200B just a couple years later.

In 2022, after over a decade of near-zero interest rates, rates began rising sharply, to around 5% today. SVB started to find itself having to pay more interest on its deposits, increasing the need for SVB to earn a return on all that money that its customers had lent it. However, most of its money was locked up in those long-term bonds, which was one problem.

The other problem, is that due to increasing rates, the funding environment for startups tightened right up—instead of investing in startups, more people were now investing in treasuries, which were yielding more than they had for over a decade (and remember, treasuries, unlike startup investments, are considered risk free). On the other hand, tech company valuations were getting slashed. This meant that as startups spent their money, no new funding was coming in to replace it. SVB’s deposits started to fall by billions of dollars as startups withdrew money to pay employees and vendors.

SVB needed to start converting some of its investments back to cash so that it could pay those customer withdrawals. Here’s where the problem started.

Most of SVB’s assets were treasuries. If those treasuries are held to maturity, SVB gets all its money back. But if it needs the money now, SVB needs to sell those treasuries now. Unfortunately, if SVB paid $100 for a treasury bond that only pays $2 in interest a year, no one today is going to buy that bond for $100 because the U.S. government is currently issuing bonds that pay $5 in interest. So if SVB sells those bonds, they are going to have to sell them for something less than $100.

This was a problem for SVB, because let’s say it sold some bonds for 95% of what they bought them for. Accounting rules require SVB to consider that its entire bond portfolio is now only worth 95% of its original value. For a $90 billion portfolio, that’s a $4.5 billion decrease. In reality, it’s reported that the bond portfolio had actually lost $15 billion in value. So if they sold some of those bonds, they would have a massive $15 billion hole in their assets that they’d have to plug somehow (remember, that’s $15 billion they no longer have to cover the deposits they’ve taken in). So those bonds were effectively untouchable in the short term.

Instead, SVB sold substantially all of its other investments for cash—$21 billion worth—it also tapped out some other lines of credit it had. As a forced seller, it incurred a $1.8 billion loss on the sale because those investments had declined in value. To plug that hole, SVB tried to do what all of its startup clients do—raise $1.75 billion equity financing. In the press release for the equity raise, the $1.8 billion dollar loss is mentioned in the last paragraph, almost as an afterthought.

People noticed, and this news spooked people. People started to wonder why SVB decided to liquidate $21 billion at a significant loss, and rumors started to fly about whether SVB was in trouble.

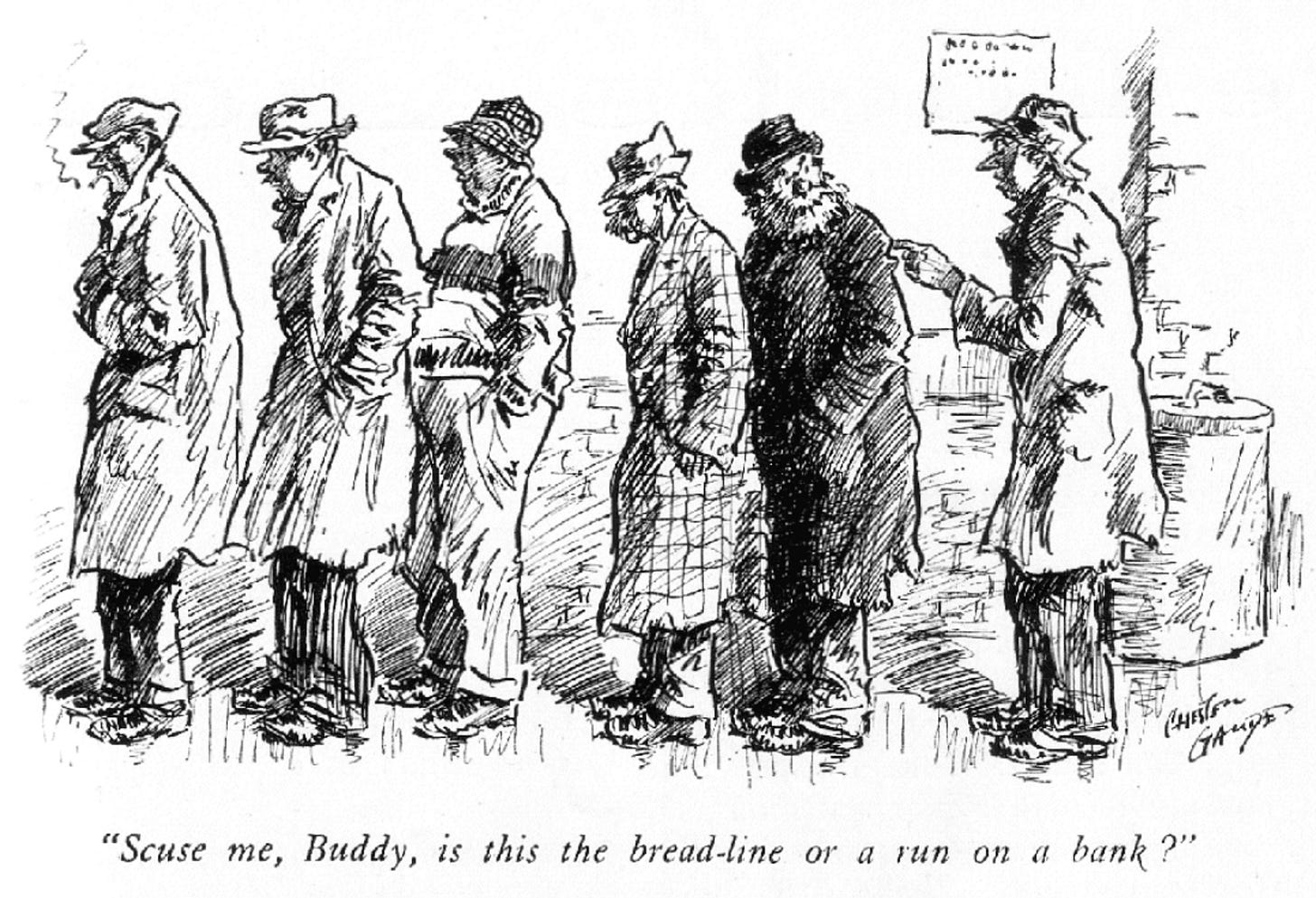

Bank Run

Silicon Valley is a pretty interconnected community and news spreads fast. For example, my CEO was plugged into his CEO and VC network and hearing what was going down. Our head of finance was talking to other heads of finance at peer companies. I was reading buzz from a mailing list with hundreds of head of legal on it. Word started circulating that companies were getting their money out of SVB, just in case. It became an echo chamber.

The other thing about having tech startups as clients is that they are tech experts, not finance experts. A large number of tech startups are run by talented under-35 founders who have not experienced a financial crisis in their professional lives, nor are they finance experts. As a result, they logically turned to their VCs for advice on what to do when the rumors started. After all, VCs are “the money guys” and they should know much more about financial management since that’s the industry they effectively operate in. So when one VC says “get your money out,” that causes a whole bunch of their portfolio companies to do just that.

Having seen how fast things unravelled in 2008 (“Bear Stearns is fine!”), my initial reaction to hearing the news was: Get your money out of SVB right fucking NOW… if you can. As in, drop whatever you’re doing and get those wire instructions in. If it’s nothing, you can always move the money back.

If you didn’t have a second bank account, or you had a loan with SVB that contractually required you to keep your cash with them, things got a bit trickier, and you then had to make calls like whether to move the cash into a founder’s personal bank account, or ignore your loan covenants, and then worry about any legal ramifications afterwards.

The next morning, and $40 billion in withdrawal requests later, SVB was dead. The FDIC announced that SVB was both insolvent and failing its regulatory liquidity requirements.

There has been some blowback against some VCs for fanning the flames of a bank run that might have been avoidable, but I don’t think VCs are to blame here. As a company, you have to look out for your own employees and business and, in this case, taking your money out if you could was the right call. If it’s a false alarm, there’s little downside. But if it’s real, then you don’t want to be stuck in a tough place… especially if it was avoidable. The herd mentality is a powerful driver of financial markets and you want to at least be part of the stampede—not be crushed by it.

What now?

Through the FDIC, the U.S. government provides deposit insurance at all FDIC-insured banks. If a bank collapses, the FDIC will ensure that depositors will be able to get at least $250,000 of their funds back. (This limit used to be $100,000 but was raised after 2008 Great Financial Crisis.) This is very helpful for the average person, who is likely to have less than $250,000 cash lying around in a bank account. It is not so helpful for a company, that is likely to have much more than that. Apparently, about 96% of SVB depositors were not fully covered by FDIC insurance, compared to about 38% at Bank of America.

This insurance kicks in very quickly. On Friday, the FDIC created a new bank called the Deposit Insurance National Bank of Santa Clara (DINB). The insured portion of all SVB bank accounts was then transferred to the new bank, and depositors will have access to those new bank accounts on Monday. The uninsured portion of those bank accounts (anything over $250K per depositor) was then effectively frozen, with the FDIC issuing a “receivership certificate” to each depositor that represents an unsecured claim on the remaining assets of SVB up to the amount of the uninsured funds.

Next, the FDIC’s job will be to sell off SVB in a way that maximizes the money they receive. That money is then distributed to a list of people, starting with secured creditors, then depositors, then other unsecured creditors, then subordinated debt holders, then anything remaining goes to SVB’s stockholders.

As the FDIC sells off SVB, it will issue a dividend to receivership certificate holders. It’s rumored that the FDIC has been hard at work flogging off tens of billions of dollars’ worth of SVB’s assets and will issue an “advance dividend” of about 50% of the value of a certificate sometime in the next week.

The best outcome now is for another bank with a strong enough balance sheet to buy SVB and assume all the deposits in one fell swoop, which will allow accounts to be unfrozen. I think that is a likely outcome. If that doesn’t happen, then SVB will be sold off in pieces, and uninsured depositors will get their money back over time. I think that depositors will get most, if not all, of their money back, but it will take months, or even years.

In the meantime, the timing uncertainty and inability to access funds is incredibly stressful to affected startups. Payroll is due next week. Failure to pay wages is one of the things that can “pierce the corporate veil”, meaning that liability for that failure spills beyond the company, and may impact officers, directors and stockholders personally. However, one would think that if employees get paid a few days late, they’re going to be understanding and not litigious.

This weekend, startups are trying to find sources of immediate-term funding, ranging from loans from VCs, bridge loans, credit cards, and selling their receivership claims at a discount to opportunistic investors.

And teams of bankers, lawyers, and bureaucrats are spending a sleepless weekend trying to figure out what to do with SVB before the markets open on Monday.

I think the majority of SVB startups will be fine at the end of the day. There may be a severe liquidity issue for startups with short runways (e.g. if you had a 12 month runway and only get 50% of your funds back next week, you now have a 6 month runway and no idea when the remainder of the money will come back, and you’re now thinking about whether you need to lay off people to conserve cash).

[UPDATE: It’s over; startups can feel relief. 30 minutes before this post was scheduled to go out: ‘The Federal Reserve, Treasury and Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation announced in a joint statement that “depositors will have access to all of their money starting Monday, March 13. No losses associated with the resolution of Silicon Valley Bank will be borne by the taxpayer.” The agencies also said that they would enact a “similar systemic risk exception for Signature Bank,” which the government disclosed was closed on Sunday by its state chartering authority.’ (per the New York Times) “Separately, the Federal Reserve announced that it was creating a new lending facility for the nation’s banks, designed to buttress them against financial risks caused by Friday’s collapse of SVB.” (per the Washington Post).]

Bail outs?

Several prominent VCs and investors have been screaming for the federal government to come in and backstop deposits in full—not just $250K. In other words, the government should effectively insure everything, and then get reimbursed as FDIC sells off SVB.

This is not a bailout of SVB. SVB is no more—its board and executive team will find themselves looking for new employment (if not already), and the equity holders will likely be wiped out.

But it is a bailout of depositors, and that has other people screaming that the U.S. taxpayer should not have to do that either. Let capitalism take its course. (And, as usual, the whole situation has been politicized.)

The issue is more nuanced than that. As I mentioned above, although depositing money at a bank is essentially lending the bank money (and therefore a form of investment), people don’t really see it like that. And you’re not really thinking that the 16th largest bank in the U.S., which has been around for 40 years and is regulated, is a credit risk. The average person on the street certainly isn’t going to be thinking about that. They’re just looking for a place to put money that isn’t under their mattress. During my time in the U.S., I have had personal bank accounts at a lot of different financial institutions (more than half a dozen), and creditworthiness was never something that crossed my mind.

So is it fair or desirable that depositors should suffer—particularly when what we are talking about here are small innovative businesses that employ thousands of people between them?

But then should we just make FDIC insurance unlimited for everyone going forward? If not, why not?

Some suggest that a failure by the government to backstop depositors here will catalyze a chain reaction that leads to catastrophic bank runs at other (small) banks. The argument goes that why would anyone put money in a smaller bank that is at risk of a bank run? People will just move money into the biggest 4 banks in the U.S., which will cause further bank runs, kill small banks, and lead to more concentration and less competition in the banking industry, which is bad for everyone. I’m not very convinced by this argument. I think we are in a specific situation exacerbated by the uniquely concentrated customer base that SVB had (only 3% retail clients!) which produced a high proportion of uninsured deposits.

This was also a liquidity issue, not a situation where SVB plowed billions into FTX stock that is now worthless and they now can’t cover the hole. SVB apparently has enough assets to cover its deposit liabilities—it just needs time to sell them off. People probably aren’t going to lose a lot of money, unlike when your crypto exchange goes belly up.

As for the question why anyone will now deposit in small banks if there’s no backstop—in most banks, the existing backstop covers most depositors. Secondly, why do people bank with smaller banks today? Because their product is positively differentiated in various ways. I’m skeptical that the perception of a potential threat of a bank run happening to a smaller bank is going to outweigh all the other reasons that smaller banks exist in a way that leads to an existential crisis for them. But let’s see what happens when the markets open on Monday.

Another thing that is clear to me is that we now have a generation of workers who have been exposed to a financial crisis for the first time. To be sure, it’s mostly localized to tech startups (for now), but for almost 15 years now, money has been cheap and free-flowing and the last 9 months have been a huge shock to the system. It will be intriguing to see how these interesting times shape the psyche of Gen Z and younger millennials, just like how the financial habits of the Silent Generation were shaped for a lifetime after growing up through the Great Depression.

More to come

I still think the worst is yet to come for the economy as a whole. If interest rates are sustained at current levels (and it’s starting to look that way, as employment is still strong and inflation remains elevated), we’ll start to see them bite into the parts of the economy that are the most sensitive to rate rises, and that will cause a domino effect. I’m not sure where that is, but I could see, for example, companies that have maturing loans getting into trouble when they have to refinance at much higher market rates. Or unrealized losses that bondholders being forced to be realized due to liquidity needs.

Buckle up.

Articles

- The Demise of Silicon Valley Bank (Net Interest)

- Startup Bank Had a Startup Bank Run (Bloomberg)

- Record Bank Run Drained a Quarter, or $42BN, of SVB Deposits in Hours (Zero Hedge)

- SVB Fallout Spreads Around World From London to Singapore (Yahoo Finance)

- 2022 letter (Dan Wang)

- The Moral Case Against Equity Language (The Atlantic)

- Who Owns the Generative AI Platform? (Andreessen Horowitz)

- Greenland Wants You to Visit. But Not All at Once. (New York Times)

- U.S. regulators rejected Elon Musk’s bid to test brain chips in humans (Reuters)

- World Nature Photography Award Winners 2002 (WNPA)

- Iceland’s Man of the Year, Haraldur Þorleifsson (Iceland Review)

- Lewis Hamilton: The F1 Superstar on Controversies, Racism, and His Future (Vanity Fair)

- The MoonSwatch Mission to Moonshine Gold Is Limited in Every Way (Wired)